SOON after Arthur Murdoch arrived on Fingal Island he was battling to come to terms with a danger he never perceived – the moody and dangerous Fingal Spit.

“The fact that it existed made our lives a bit more hazardous,” Arthur said.

“If it had been an island everyone would have accepted island life, and would have made their crossings to the mainland by boat; they would have accepted that rough seas would keep them on the island.”

Arthur developed a great respect for the sandy finger that occasionally connected the island to the mainland.

He was well aware that the sand spit to the island governed the lives of everyone who lived and worked around the Outer Light.

Over his ten or so years of crossing, he estimated between 300-400 times, he witnessed many moods.

“A big sea from the south washes the sand north and a big sea from the north washes the sand into Fingal Bay,” he said.

“No matter how badly the spit is cut open, it will always build up again.”

Not everyone was as respectful of the dangers that the spit posed.

Early in his stay Arthur remembered the well-liked Lightkeeper Morgan.

Morgan did not understand the Spit and he was also partial to a drink when he visited Nelson Bay for supplies. Rather than returning on time to cross the Spit in safety, as Murdoch had suggested, Morgan came later and had been swamped by the waves and lost all the family’s supplies.

He was fortunate not to have lost more.

On the island Arthur originally moved into a roughly constructed fisherman’s shed built years earlier by Walter Glover. Later he took up residence in the Lighthouse shed in the corner of the beach.

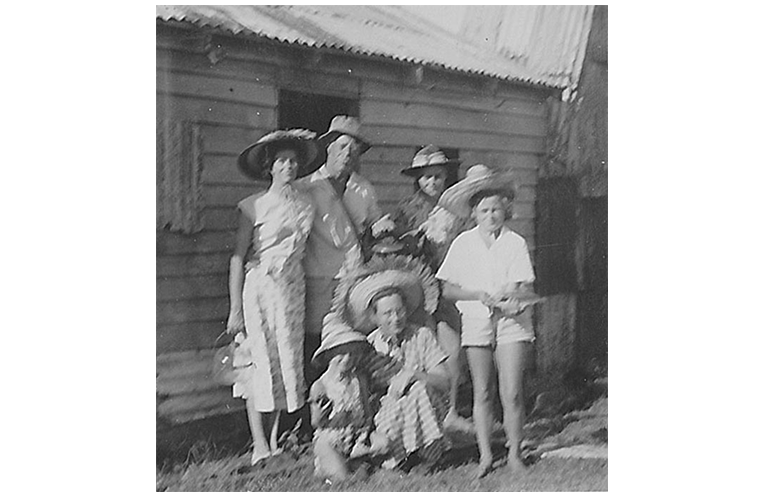

Finally in 1935 he built a shack of his own on the rise above Crayfish Hole which was described by family friend Deidre Calvert as “rudimentary with almost two rooms”.

“After the big gale of 1932, I thought, ‘I’ll build myself a new hut’,” Arthur said.

“Now, in July 1935, I at last made a start.

“I’d picked a site overlooking Crayfish Hole and the lighthouse wharf, and the view north, of headlands and beach and islands, was one of the finest in the world,” reckoned Arthur.

With a touch of irony, Arthur used salvaged parts of the Pappinbarra, that washed ashore, to build his hut.

“I used the heavy deck timbers and hatch covers as part of my new hut when I built it in 1935.”

Back on the beach Arthur commented on being attracted to a light in the far corner of Fingal Beach.

“I could see a dim light across the water in Fingal Bay corner.

“On inquiring from the fishermen I was told a young man, Jack Barry, with a wife and baby son had come to live.

“They had built a hut and were going to see out the Depression living there.”

During the early period of the venture, local fisherman Jack Lund had been ferrying the bagged shell grit from Shelley to the Nelson Bay wharf in his launch where it was transferred onboard the Coweambah for the trip to Newcastle. This method had problems which were overcome by a suggestion from Jack Lund to ferry the grit from the island to Salt Ash by boat.

As a result two old 26 foot Naval cutters were purchased for £25.

The plan was to load the cutters with shell grit and tow them, with Jack Lund’s launch, through the heads, into the port and up past Nelson Bay to Salt Ash where they could be off-loaded for transport by truck to Newcastle.

It was necessary to wait for a south wind which would blow them to the entrance of the port and a run-in tide that would assist their travel to Salt Ash.

Jack Lund, rising 50 years of age, retired after working with Arthur for six years from 1930.

Jack and his wife moved to Newcastle where he worked on the wharves until the end of the Second World War.

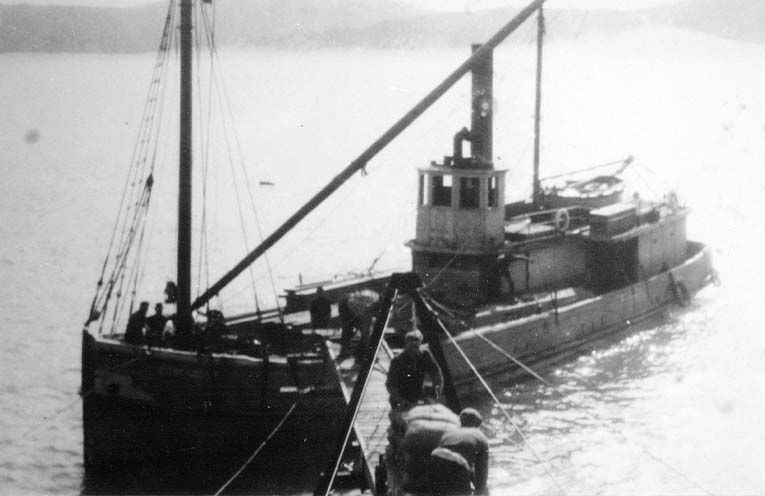

Another bright idea, this one from old Walter Laman, was as follows: “What would prevent the Cowie from being loaded directly from the southern lease without dinghies? If you built a ramp, a wharf that would reach out into deep water?”

Bill Ripley, skipper of the Coweambah, was interested but sceptical.

Soon after the mighty Coweambah was commandeered by the Naval authorities for the war effort and sailed off to New Guinea – with Bill Ripley at the helm.

The proud old boat lived right through the worst of the war.

Then, in charge of a naval crew, she was wrecked on a North Coast beach on her way home.

“It wouldn’t have been wrecked if Ripley was at the wheel,” Arthur said.

Arthur was full of admiration for the Coweambah.

Point Stephens became a focus of defence during the war years as it was considered that the Japanese forces considered the area as strategically essential for the invasion of Australia.

By 1942 the island had become fortified and troops were stationed across the island.

To his great displeasure, Arthur was barred from what he considered to be his own island.

During the war years Arthur was told to leave the island by the soldiers for security reasons.

Family friend Deidre Calvert believes that the Army was annoyed because Arthur told the soldiers not to stir their cups of tea with oleander sticks from the trees that grew on the island.

The soldiers took no notice of Arthur’s warning and as a result they all got narky when they all got sick from the oleander.

By John ‘Stinker’ CLARKE